There are places on this planet where the map feels strained—where the continent tapers into something thin and improbable, where the very idea of a “human-habitable world” feels like a fragile negotiation between geology and stubborn human will. Chile is one of those places. The Mapuche knew what they were talking about: “Chilli” is often translated as “where the land ends.” Chile is a long, ribbon of earth clinging to the side of a continent, daring you to follow its length. And since I have a particular fondness for walking along the quiet edges of the world in search of all manner of critters, it was too much of a temptation to resist. So last August, I crossed hemispheres—trading Edmonton’s summer for Chile’s winter—and stepped onto a long, narrow blade of earth pressed between the largest ocean and the longest continental mountain range on the planet: a country balanced on a literal and metaphorical knife’s edge.

Chile: a thin red blade stitched to the western edge of South America—one country, nearly every climate. It’s hemmed in on all four sides: the Pacific seals the west; the Andes wall off the east; the Atacama Desert acts as a harsh ecological gatekeeper to the north; and to the south, Patagonia dissolves into fjords and the storm-battered Southern Ocean, where the continent finally breaks apart. No labels needed—its borders are written in water, rock, and wind.

Chile is a biogeographic island perilously lashed to the side of South America, isolated in all four directions by barriers that shape everything from range limits to endemism. To the west lies the Pacific—an ocean so vast it rewires your sense of scale. Standing on the coast in Cachagua, a few hours north of Valparaíso, scanning for Humboldt Penguins with wind-driven salt in my face, it felt like seawatching at the edge of the world: steel-blue, bottomless, and indifferent. From roughly 33°S, the next major landfall due west is Australia—on the order of 12,700 km away—an absurd distance that puts the isolation of this coast into perspective. To the east, the Andes rise as a jagged spine: the longest continental mountain range on Earth, with peaks over 6,000 m and high-elevation deserts and wetlands around 4,500 m, where the air itself becomes a limiting factor. To the north, the Atacama—vast, hyper-arid, and in many places high—functions as a near-insurmountable ecological barrier as real as any ocean, constraining movement and compressing life into rare oasis of water and vegetation. Finally, to the south, Chile tapers into the end of the continent and the violence of the Southern Ocean—Patagonia giving way to the Drake Passage—another boundary that is less a line on a map than a fundamental ecological divide. Chile’s most obvious turnover is the strong latitudinal gradient (north–south), but the revelation in the field was the longitudinal gradient (west–east): here, an afternoon’s drive can feel like a crossing between planets.

The birding began in earnest on the coast in the sleepy village of Cachagua, where the primary target was Humboldt Penguins that often loaf on a tiny rocky island just offshore. Isla Cachagua is close enough to allow one to easily observe its local feathered inhabitants from the mainland, but just far enough to keep people from simply wading over and ruining it.

From the coast, the road veered inward, cutting through the matorral—those sun-toughened scrublands that stretch across central Chile like an ancient memory. Narrow valleys carved into the mountains feel like scars: deep, ageless, reminders of tectonic violence and water’s patient insistence. We followed those valleys north, and with each bend the country subtly changed—light sharpening, air drying, slopes steepening—while we kept scanning the hills, the wires, the roadside scrub, the sky.

Farther north, the country begins to feel like it is shedding moisture and mercy. The desert doesn’t arrive all at once—it advances in increments, reclaiming greens, simplifying the palette, hardening the light. By the time you reach Parque Nacional Pan de Azúcar (Sugar Loaf National Park)—named for the offshore Isla Pan de Azúcar, whose guano-whitened rock was said in 19th-century accounts to resemble the old “sugar loaves” shipped as white blocks—the Atacama doesn’t so much meet the Pacific as collide with it.

Pan de Azúcar is the embodiment of contradiction: the driest desert on Earth crashing into one of the richest oceans. The cold Humboldt Current drives nutrient-rich upwelling offshore and rolls in fog (locally known as the camanchaca) that looks like mercy but rarely delivers rain—moisture without relief, a thin, silvery lifeline in a landscape that gets almost none. The desert stays severe right to the edge: sun-bleached slopes breaking abruptly into cold, steel-blue depths. Cacti cling to cliffs above seabirds riding the wind, guanacos drift across barren ridgelines, and life persists in the narrowest of margins—aridity fed by fog, abundance hidden beneath hostile surfaces.

Eventually the shift becomes unmistakable. Green retreats. Sand and stone take over. The light turns whiter, harsher, more honest. We were now properly inside the Atacama: one of the world’s highest and driest deserts.

There is so much more to explore in this remarkable part of the world, but two specific items we was not able to check off my bucket list this time around were El Desierto Florido—the “flowering desert”—and the elusive Diademed Sandpiper-Plover.

As the matorral transitions to the Atacama, in years when the austral winter rains are unusually strong, dormant seeds burst into life, covering the landscape in carpets of purple, pink, yellow, and white. It’s brief, unpredictable, and spectacular—an explosion of color in a place that is normally defined by silence, salt, and stone. I thought I had timed everything perfectly to bear witness to this phenomenon, but nature does not follow an itinerary. This time around, for reasons unknown, El Desierto Florido was late by about a month and by the time it arrived I was long gone.

The second item we were not able to cross off was the Diademed Sandpiper-Plover (Phegornis mitchellii) aka referred to as the DSP among birding Uber nerds and locally known as Chorlo Cordillerano. After a few thousand kilometers—or maybe it was the thin air—we started calling it El Pollito (the little chicken). El Pollito looks like a diminutive shorebird with its long bill and long legs, except it doesn’t live at the shore. It lives on a razor-thin line between earth and sky—an elusive jewel of the high-Andean bogs, wearing a crown of silver feathers and appearing only to those willing to search where most birds, and most people, never dare to go. It is a rare and coveted find among birders. We certainly put in the miles chasing it. It certainly refused to appear.

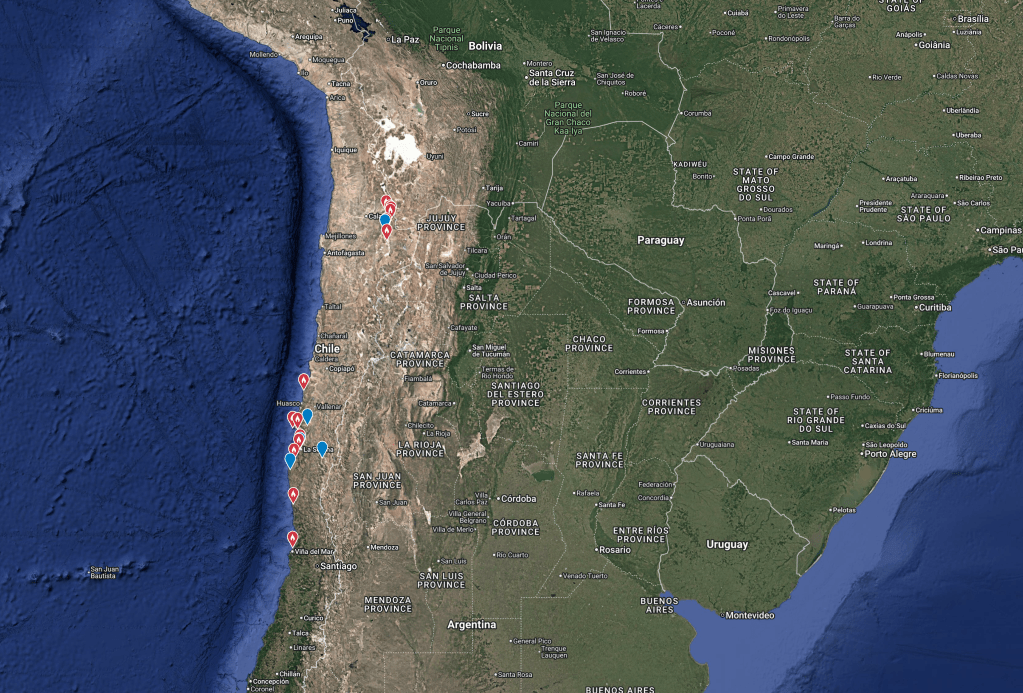

By the time we turned south again, swinging back toward Santiago and sea level, we had travelled close to 5,000 km—a journey measured not only by distance but by gradients: altitude, light, wind, silence, and, of course, birds. For the full, site-by-site accounting—every checklist, every species, and the exact locations—the complete record is available as an eBird trip report.

So we never got to see El Desierto Florido or El Pollito. But perhaps leaving a few wants hanging has a silver lining: it gives me two more reasons (not that I need them) to return to this magical country at the edge of the world. In the meantime, I’m back on my home turf, and to borrow the words of Chilean poet Pablo Neruda: ‘I returned from my travels; I sailed on, building joy.’

May the curiosity be with you. This is from “The Birds are Calling” blog (www.thebirdsarecalling.com). Copyright Mario Pineda.